MIT App Inventor Summer Appathon recap

This summer I participated in the MIT App Inventor Summer Appathon, which the official website described as “a marathon-like event to build apps.” As my first year in the event, I built a simple app that generates stories for children with AI power. And to my big surprise, I actually earned an Honorable Mention! In this post, I will describe what I did, how I did it, and what I learned. Let’s get started!

Preface: What is MIT App Inventor?

MIT App Inventor’s official website says this:

MIT App Inventor is an intuitive, visual programming environment that allows everyone – even children – to build fully functional apps for Android phones, iPhones, and Android/iOS tablets.

And that’s exactly what it is! App Inventor uses a Scratch-like programming interface that allows creating mobile apps without writing a single line of code.

There are obvious pros for this no-code application-building process.

- It’s easy to use. You just drag blocks and make apps. Simple as that.

- Many features are encapsulated into “components.” No more worrying about clocks, layouts, web APIs (foreshadowing: like OpenAI), activities or whatnot – everything is available as simple blocks: events, methods, and properties.

However, this also means there are some cons too.

- Try writing complicated logic with Scratch, and you’ll know the pain. Imagine chaining 5 and-blocks on one line, each with some comparison, list operations, and math!

- For programmers, it feels redundant to drag blocks around. Typing is much faster than moving the mouse.

This is why, in addition to writing my app, I also wrote a library that helps me write blocks. More on that later!

My idea: Story Box

Watch this video to find out about my app!

Coding in App Inventor: py2ai

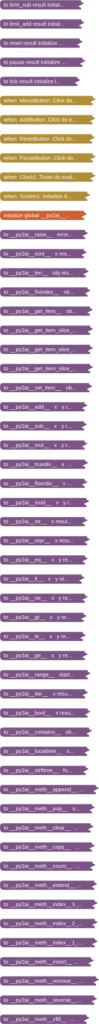

Initially I tried to write the code in pure App Inventor blocks. Soon I realized that this is quite impossible: the logic is simply too much! So I had two choices: either bear with the blocks and deal with the pain (no offense, App Inventor), or do something about it. Naturally, I chose the more fun option, and I did something about it, in the form of a Python library: py2ai. Check it out on GitHub here!

Basically, you use pure Python to write code, which will then be translated into App Inventor components and blocks. Pretty cool, huh?

This is some example code for a simple timer application that counts upward and vibrates the phone when it hits a certain configurable threshold:

from py2ai.magic import *

from py2ai.components import *

Screen1 = Form(BigDefaultText=True)

Spacing1 = HorizontalArrangement(Height=10, Width=-2)

LimitRow = HorizontalArrangement(AlignVertical=2, Width=-2)

LimitLabel = Label(parent=LimitRow, FontBold=True, Width=100, Text='Limit')

MinusButton = Button(parent=LimitRow, Width=48, Text='-')

LimitInput = TextBox(

parent=LimitRow, Height=-2, Width=-2, NumbersOnly=True, Text='60', TextAlignment=1

)

AddButton = Button(parent=LimitRow, Width=48, Text='+')

CounterLabel = Label(FontSize=100, Width=-2, Text='0000', TextAlignment=1)

ResetButton = Button(FontSize=70, Height=240, Width=-2, Text='Start')

PauseButton = Button(Height=100, Width=-2, Text='Pause/Resume', Visible=False)

OptionsRow = HorizontalArrangement(AlignVertical=2, Width=-2)

OptionsLabel = Label(parent=OptionsRow, FontBold=True, Width=100, Text='Options')

VibrateCheckbox = CheckBox(parent=OptionsRow, Checked=True, Width=-2, Text='Vibrate')

BeepCheckbox = CheckBox(parent=OptionsRow, Checked=True, Width=-2, Text='Beep')

Sound1 = Sound(Source='beep.wav')

Clock1 = Clock(TimerEnabled=False)

def limit_sub():

LimitInput.Text = str(max(int(LimitInput.Text) - 15, 0))

def limit_add():

LimitInput.Text = str(int(LimitInput.Text) + 15)

def reset():

ResetButton.Text = 'Reset'

Clock1.TimerEnabled = True

PauseButton.Visible = True

CounterLabel.Text = '0000'

def pause():

Clock1.TimerEnabled = not Clock1.TimerEnabled

def tick():

tim = int(CounterLabel.Text) + 1

if tim >= int(LimitInput.Text):

if BeepCheckbox.Checked:

Sound1.Play()

if VibrateCheckbox.Checked:

Sound1.Vibrate(500)

if tim < 10:

CounterLabel.Text = '000' + str(tim)

elif tim < 100:

CounterLabel.Text = '00' + str(tim)

elif tim < 1000:

CounterLabel.Text = '0' + str(tim)

else:

CounterLabel.Text = str(tim)

MinusButton.on_Click(limit_sub)

AddButton.on_Click(limit_add)

ResetButton.on_Click(reset)

PauseButton.on_Click(pause)

Clock1.on_Timer(tick)

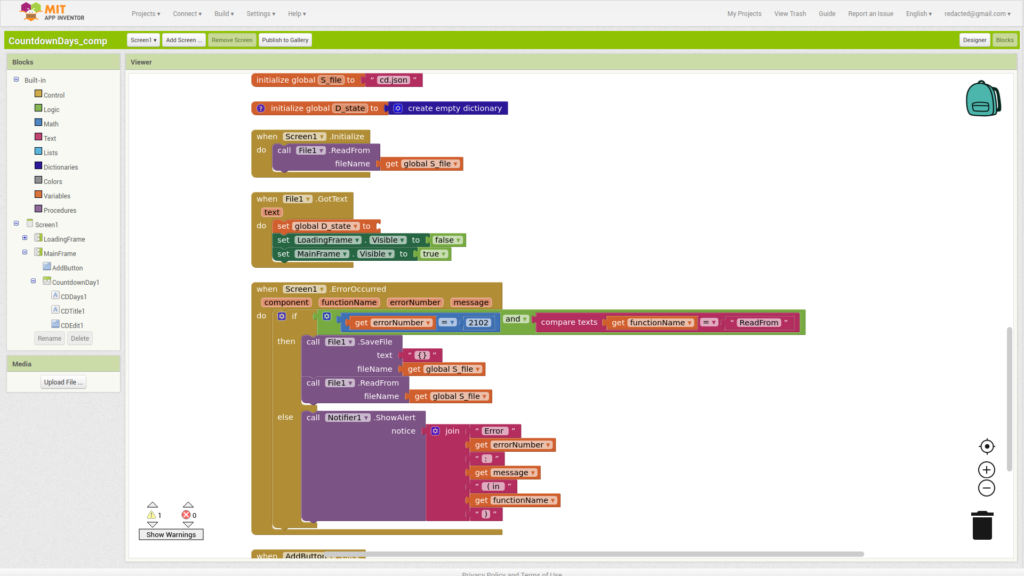

And this will compile to this App Inventor application:

Which is a huge mess. This is because I wrote a set of App Inventor procedures (functions) that each correspond to (more or less) one Python dunder method: __int__, __getitem__, __len__, etc.

Now the interesting part: how on earth did the Python code get converted to these App Inventor blocks?

I’m glad you asked.

I used the Python builtin module ast, which parses the Python syntax into an Abstract Syntax Tree. I then need to traverse each item in the tree and convert them to approximately one block each.

It’s a big pain.

For each AST type (List, ListComp, Call, Assign, AnnAssign, …), I need to make a compiler function for it. This is why if you open the compiler.py file on GitHub, you will see a huge file with a million methods prefixed with visit_ and the AST node name.

But I wrote enough visit methods to make the compiler work, and I then wrote my Story Box app in Python. The source code for that is also on GItHub.

App Logic

The logic is pretty much all said in the 2-minute video above. The user creates stories by filling in details, including theme, style, and main character, then ChatGPT is used to generate the story based on these details. The user can ask ChatGPT to continue generating where it left off, and on the home page, they can also view all the stories they have created.

If you want to see some screenshots, check out the video above!

Conclusion

I didn’t actually expect to get a prize or anything. So when the finalist names came out, and in the Youth Individual track I can’t find “Story Box,” I wasn’t that surprised. After all, the code is super ugly, the app is simple, and there’s almost no art.

However, when the final announcements came out, I checked the results, and I saw Story Box, right there, in the Honorable Mentions list! True, it’s not as good as finalist, but heck, at least that’s something!

From this experience, I learned that it can be useful to convert a problem into another. Although the process might take some (a lot) of time, in the end, I learned from it and enjoyed the result. Above all, I learned that it never hurts to try. And if I keep on trying, maybe next year I’ll end up as a finalist. Who knows? 😉